Veteran signaller Alan Hayward has put up a commemorative sign reading 1896-2017 in one window and is already counting down the handful of shifts he still has to work in Poulton No 3 Signal Box before its final closure – and his early retirement – in less than two months’ time, on Saturday, 11 November.

Veteran signaller Alan Hayward has put up a commemorative sign reading 1896-2017 in one window and is already counting down the handful of shifts he still has to work in Poulton No 3 Signal Box before its final closure – and his early retirement – in less than two months’ time, on Saturday, 11 November.

Like four other remaining signal boxes on the 17.5-mile route from Preston to Blackpool North, the last of what were once five signal boxes at Poulton-le-Fylde will be swept away as the route is closed for its long-awaited electrification and re-signalling, a transformation set to take until at least next May to be completed. Continue reading “A Signalman’s Farewell”

Like four other remaining signal boxes on the 17.5-mile route from Preston to Blackpool North, the last of what were once five signal boxes at Poulton-le-Fylde will be swept away as the route is closed for its long-awaited electrification and re-signalling, a transformation set to take until at least next May to be completed. Continue reading “A Signalman’s Farewell”

Work is expected to begin early next year on an ambitious £1 million eight-month long project to restore the historic Rewley Road Swing Bridge at Oxford, more than 30 years after the last freight train trundled across it in May 1984. Despite having long since lost its rail services, the bridge remains owned by Network Rail and stands close to the main railway line just north of Oxford station.

Work is expected to begin early next year on an ambitious £1 million eight-month long project to restore the historic Rewley Road Swing Bridge at Oxford, more than 30 years after the last freight train trundled across it in May 1984. Despite having long since lost its rail services, the bridge remains owned by Network Rail and stands close to the main railway line just north of Oxford station. Looking at the massive success of London Overground in reinvigorating rail corridors around the capital, such as the North London, East London and South London Lines, it is perhaps remarkable that there is one short stretch of line in North London where time has seemingly stood still, with control by semaphore signals and a sparse traffic comprising the occasional slow-moving freight train and empty stock movements between the capital’s termini.

Looking at the massive success of London Overground in reinvigorating rail corridors around the capital, such as the North London, East London and South London Lines, it is perhaps remarkable that there is one short stretch of line in North London where time has seemingly stood still, with control by semaphore signals and a sparse traffic comprising the occasional slow-moving freight train and empty stock movements between the capital’s termini. More that three years after its March 2014 suspension, (see my earlier post “Last steam to Leszno”) scheduled standard gauge steam returned to Europe in May 2017, when two return weekday services from Wolsztyn to Leszno in Western Poland returned to steam haulage.

More that three years after its March 2014 suspension, (see my earlier post “Last steam to Leszno”) scheduled standard gauge steam returned to Europe in May 2017, when two return weekday services from Wolsztyn to Leszno in Western Poland returned to steam haulage. This followed the agonisingly slow setting up of a trust to own and manage the famous steam depot at Wolsztyn, the return to traffic of two locomotives and the sourcing of suitable coaches to operate the service, which should also see two Saturday round trips between Wolsztyn and Poznan, once track renewal work has been completed later this year.

This followed the agonisingly slow setting up of a trust to own and manage the famous steam depot at Wolsztyn, the return to traffic of two locomotives and the sourcing of suitable coaches to operate the service, which should also see two Saturday round trips between Wolsztyn and Poznan, once track renewal work has been completed later this year.  When Network Rail was completing a £67 million project to re-double two sections of the Cotswold Line between Oxford and Worcester in 2011 there was not enough left in the kitty to re-signal the two re-doubled stretches of line – four miles from Charlbury to Ascott-under-Wychwood and 16 miles of line from Moreton-in-Marsh to Evesham.

When Network Rail was completing a £67 million project to re-double two sections of the Cotswold Line between Oxford and Worcester in 2011 there was not enough left in the kitty to re-signal the two re-doubled stretches of line – four miles from Charlbury to Ascott-under-Wychwood and 16 miles of line from Moreton-in-Marsh to Evesham. Rail-borne visitors to the UK’s 2017 city of culture could probably be forgiven for failing to spot during the latter stages of their journey what many enthusiasts would describe as some of the finest remaining semaphore signalling in England. It survives on a 9.5 mile stretch of line between Gilberdyke Junction and North Ferriby, but is being swept away in a £34.5 million upgrading project, due for completion in Spring 2018.

Rail-borne visitors to the UK’s 2017 city of culture could probably be forgiven for failing to spot during the latter stages of their journey what many enthusiasts would describe as some of the finest remaining semaphore signalling in England. It survives on a 9.5 mile stretch of line between Gilberdyke Junction and North Ferriby, but is being swept away in a £34.5 million upgrading project, due for completion in Spring 2018. My nationwide quest to photograph Britain’s last mechanical signalling, in connection with a new book project, has brought me back to the Settle & Carlisle line, that amazing 72 miles of line between Settle in North Yorkshire and Carlisle in Cumbria, which 30 years ago was under sentence of death.

My nationwide quest to photograph Britain’s last mechanical signalling, in connection with a new book project, has brought me back to the Settle & Carlisle line, that amazing 72 miles of line between Settle in North Yorkshire and Carlisle in Cumbria, which 30 years ago was under sentence of death. Sri Lanka’s extensive broad gauge (5’ 6”) railway network not only boasts a great deal of classic mechanical signalling (see my earlier “Eye Kandy” post) but also offers some magnificently scenic rail journeys at absurdly cheap fares, and an interesting variety of rolling stock, imported from places as far afield as the US and Japan.

Sri Lanka’s extensive broad gauge (5’ 6”) railway network not only boasts a great deal of classic mechanical signalling (see my earlier “Eye Kandy” post) but also offers some magnificently scenic rail journeys at absurdly cheap fares, and an interesting variety of rolling stock, imported from places as far afield as the US and Japan. Citizens of Nottingham, Leicester and Derby now know the true cost of High Speed Two. After an endless on/off saga they now know that they will not be able to travel on modern high speed electric trains to the capital and that their Midland Main Line will become the only major route from London that is not electrified.

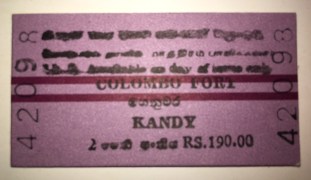

Citizens of Nottingham, Leicester and Derby now know the true cost of High Speed Two. After an endless on/off saga they now know that they will not be able to travel on modern high speed electric trains to the capital and that their Midland Main Line will become the only major route from London that is not electrified. Take a three hour train trip from Colombo’s Fort station to Sri Lanka’s second city, Kandy, and there are plenty of reminders of the amazing legacy which Victorian railway pioneers left to this former outpost of the British Empire. While the train itself is likely to be one of the modern Chinese-built S12 diesel units dating from 2012, the bargain priced ticket (190 Rupees second class, or just under £1.00) will be a classic Edmondson card, like all the tickets issued at ticket offices throughout the country.

Take a three hour train trip from Colombo’s Fort station to Sri Lanka’s second city, Kandy, and there are plenty of reminders of the amazing legacy which Victorian railway pioneers left to this former outpost of the British Empire. While the train itself is likely to be one of the modern Chinese-built S12 diesel units dating from 2012, the bargain priced ticket (190 Rupees second class, or just under £1.00) will be a classic Edmondson card, like all the tickets issued at ticket offices throughout the country.

You must be logged in to post a comment.